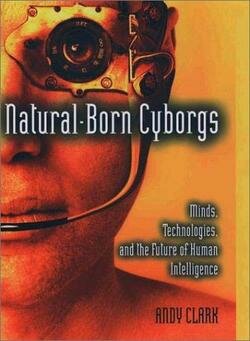

The author of Natural-Born Cyborgs, Andy Clark, is more philosopher than science fiction writer, though as the cover indicates he does cover some pretty far out technology in this book. He’s most interested in the notion of the ‘expanded mind’, by that meaning the way we incorporate not only biological but also technological tools to navigate in the world. By this he means not just the cinematic cyborg concepts like implants into the brain, but also simpler tools like pen and paper, and anything else we use either consciously or unconsciously. I found this book really interesting for a number of reasons, and I’ll try to cover a few high points.

1. On language:

“The deepest contributions of speech and language to human thought, however, may be something so large and fundamental that it is sometimes hare to see it at all! For it is our linguistic capacities, I have long suspected, that allow us to think and reason about our own thinking and reasoning. And it is this capacity, in turn, that may have been the crucial foot-in-the-door for the culturally transmitted process of designer-environment construction: the process of deliberately building better worlds to think in.” (p. 78). What he’s getting at here is language as a tool that gives us the ability to examine concepts and generate ideas that could not have been conceived of without language.

In a somewhat similar fashion he mentions how we use mathematical shortcuts and paper-based tools to, for example, multiply two large numbers, like 147 * 382. Most of us cannot do that calculation in our heads, but with a piece of paper and a pencil and the mental math tools of breaking the problem down into simple integer multiplication (7 * 2, then 7* 8, etc.) we can solve the problem. So is the calculation simply in our head, or is it in fact a collaboration of brain and pencil and paper (or these days brain and calculator). The tools expand our mental universe, give us access to areas that we could not get to without them.

2. On extended mental worlds, Alzheimer’s example:

“These patients were a puzzle because although they still lived alone, successfully, in the city, they really should not have been able to do so. On standard psychological tests they performed rather dismally. They should have been unable to cope with the demands of daily life. What was going on? A sequence of visits to their home environments provided the answer. These home environments, it transpired, were wonderfully calibrated to support and scaffold these biological brains. The homes were stuffed full of cognitive props, tools and aids. Examples included message centers where they stored notes about what to do and when; photos of family and friends complete with indications of names and relationships; lables and pictures on doors; [etc.]” (p. 140).

Here again he is making the point that we put ‘intelligence’ out in our environment, and our brains and bodies work with these tools to make sense of the world. Note that none of this involves ‘biological implants’ but in principle these too are tools that can feed us more useful information, just the way a cane can provide information to a blind person.

3. The extended mind:

“What we really need to reject, I suggest, is the seductive idea that these various neural and nonneural tools need a kind of privileged user. Instead, it is just tools all the way down. Some of those tools are indeed more closely implicated in our conscious awareness of the world than others. But those elements, taken on their own, would fall embarrassingly short of reconstituting any recognizable version of a human mind or an individual person. Some elements, likewise are more important to our sense of self and identity than others. Some elements play larger roles in control and decision making than others. But this divide, like the ones before it, tends to crosscut the inner and the outer, the biological and the nonbiological.” (p 137).

“Tools-R-Us. But we are prone, it seems, to a particularly dangerous kind of cognitive illusion. Because our best efforts at watching our own minds in action reveal only the conscious flow of ideas and decisions, we mistakenly identify ourselves with the stream of conscious awareness.” (p. 137).

There is plenty more to chew on in this book. This argument about the extended mind is similar to the points made by Alva Noe in his book Out of Our Heads.

1. On language:

“The deepest contributions of speech and language to human thought, however, may be something so large and fundamental that it is sometimes hare to see it at all! For it is our linguistic capacities, I have long suspected, that allow us to think and reason about our own thinking and reasoning. And it is this capacity, in turn, that may have been the crucial foot-in-the-door for the culturally transmitted process of designer-environment construction: the process of deliberately building better worlds to think in.” (p. 78). What he’s getting at here is language as a tool that gives us the ability to examine concepts and generate ideas that could not have been conceived of without language.

In a somewhat similar fashion he mentions how we use mathematical shortcuts and paper-based tools to, for example, multiply two large numbers, like 147 * 382. Most of us cannot do that calculation in our heads, but with a piece of paper and a pencil and the mental math tools of breaking the problem down into simple integer multiplication (7 * 2, then 7* 8, etc.) we can solve the problem. So is the calculation simply in our head, or is it in fact a collaboration of brain and pencil and paper (or these days brain and calculator). The tools expand our mental universe, give us access to areas that we could not get to without them.

2. On extended mental worlds, Alzheimer’s example:

“These patients were a puzzle because although they still lived alone, successfully, in the city, they really should not have been able to do so. On standard psychological tests they performed rather dismally. They should have been unable to cope with the demands of daily life. What was going on? A sequence of visits to their home environments provided the answer. These home environments, it transpired, were wonderfully calibrated to support and scaffold these biological brains. The homes were stuffed full of cognitive props, tools and aids. Examples included message centers where they stored notes about what to do and when; photos of family and friends complete with indications of names and relationships; lables and pictures on doors; [etc.]” (p. 140).

Here again he is making the point that we put ‘intelligence’ out in our environment, and our brains and bodies work with these tools to make sense of the world. Note that none of this involves ‘biological implants’ but in principle these too are tools that can feed us more useful information, just the way a cane can provide information to a blind person.

3. The extended mind:

“What we really need to reject, I suggest, is the seductive idea that these various neural and nonneural tools need a kind of privileged user. Instead, it is just tools all the way down. Some of those tools are indeed more closely implicated in our conscious awareness of the world than others. But those elements, taken on their own, would fall embarrassingly short of reconstituting any recognizable version of a human mind or an individual person. Some elements, likewise are more important to our sense of self and identity than others. Some elements play larger roles in control and decision making than others. But this divide, like the ones before it, tends to crosscut the inner and the outer, the biological and the nonbiological.” (p 137).

“Tools-R-Us. But we are prone, it seems, to a particularly dangerous kind of cognitive illusion. Because our best efforts at watching our own minds in action reveal only the conscious flow of ideas and decisions, we mistakenly identify ourselves with the stream of conscious awareness.” (p. 137).

There is plenty more to chew on in this book. This argument about the extended mind is similar to the points made by Alva Noe in his book Out of Our Heads.

No comments:

Post a Comment